Sixty-four African organisations and individuals, working in various fields in addressing Africa’s development challenges, have welcomed the withdrawal of British politician Matt Hancock as a special envoy of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

They expressed fears over what they said could be a “damaging fall out from the failed attempt of the appointment.”

In a statement, the 64 signatories expressed worry over the consequences and lessons of that appointment, saying the Hancock debacle has damaged the UNECA and the credibility and standing of its Executive Secretary, Ms. Vera Songwe.

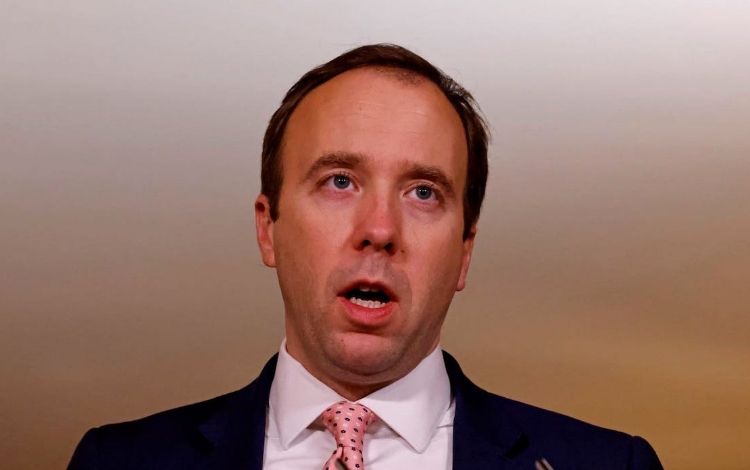

Mr. Matt Hancock, a former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care and MP for West Suffolk, had been appointed as Special Representative for Financial Innovation and Climate Change of UNECA.

Below is a copy of the statement and the signatories

The Hancock debacle has damaged the UNECA and the credibility and standing of its Executive Secretary Ms. Vera Songwe

We, the undersigned African organizations and individuals welcome the withdrawal, by the UN Secretary General, of the appointment of Mr. Matt Hancock, former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care and MP for West Suffolk as Special Representative for Financial Innovation and Climate Change of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

The decision of Ms. Vera Songwe, the Executive Secretary of the UNECA, to appoint Mr. Hancock was disgraceful to and disdainful of all Africans.

The appointment was a grave error of judgement by Ms. Vera Songwe and the rescinding of the appointment is a severe rebuke to her.

In the letter appointing Mr. Hancock, Ms. Vera Songwe reportedly praised his “success on the U.K.’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the acceleration of vaccines that has led the U.K. to move faster toward economic recovery is one testament to the strengths that you will bring to this role”.

The announcement of Mr. Hancock’s appointment and disclosure of Ms. Songwe’s effusive appraisal of his record as UK Health Secretary and potential value to Africa coincided with the release of a UK Parliamentary report which was highly critical of his handling of the UK’s Covid 19 pandemic.

Mr. Hancock resigned from the UK government in June under a cloud amidst accusations of hypocrisy after being caught on security cameras in his office, breaching the government’s Covid-19 distancing rules, clinching with an aide with whom he was having

an affair.Mr. Hancock was also mired in corruption allegations during his tenure as Health Secretary.

Ms. Vera Songwe’s ill-judged decision to appoint Mr. Hancock and her celebration of his competence and value in the face of evidence to the contrary are beyond parody.

It is likely the widespread condemnation of Mr. Hancock’s appointment was an important influence on the decision of the UN Secretary General to override it.

The negative reactionsranged from bewilderment to angry denunciations of the disrespectful dumping on Africa of a disgraced politician whose competence has been questioned in his own country and who knows little about Africa.

See Telegraph – fury greets matt-hancock un appointment; Guardian – Matt Hancock appointed UN special envoy; Independent Hancock appointment; Unserious Hancock appointment questioned.

The Hancock affair constitutes a betrayal of the best traditions of the UNECA as an institution which strives to reinforce and strengthen Africa’s autonomous policy making, and independent presence and voice on the world stage. Unfortunately, it is the latest

in a series of acts that show Ms. Songwe’s lack of proper understanding of or regard for the history of the UNECA and a thinly veiled contempt for African institutions.

It fits into a history of incidents and acts involving Ms. Songwe which have degraded the UNECA’s role, developed and advanced by previous Executive Secretaries, as an institution serving African interests.

Under Ms. Songwe’s leadership there has been a marked pivot by the UNECA away from the consultative and collaborative relations with the African Union which have been the centrepiece of a strategic engagement among the key pan-African inter-governmental institutions, in which the African Development Bank is also a key pillar.

The IMF and World Bank and their power universe have become a more important reference point. UNECA staff talk about the incredible amount of time the Executive Secretary spends travelling to cement her links in these power circles.

Structures and relations for pan-African collaboration have been largely hollowed out.

Mr. Hancock’s aborted appointment is illustrative of these negative shifts.

The UNECA announcement of his appointment said he “will further the UN’s work in supporting Africa’s path to recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic by incentivising financial investment into sustainable economic development, working with organisations like the IMF, G20 and COP26 in partnership with the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa.”

This role duplicates decisions and processes already initiated by the African Union. In April 2020, the then chairperson of the African Union, President Ramaphosa of South Africa, appointed four internationally renowned Africans as special envoys to help “mobilise international support for Africa’s efforts to address the economic challenges African countries will face as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

They have been tasked with soliciting rapid and concrete support as pledged by the G20, the European Union and other international financial institutions.

See African Union announces special envoys.

Besides Mr. Hancock’ patent unfitness for the role he was offered, the existence of these four AU envoys raises questions about how his role would have fitted in the architecture of African outreach initiatives in support for economic recovery from the Covid 19 pandemic.

Staff of the UNECA were reportedly bemused but not surprised by Matt Hancock’s appointment seeing it as the latest example of a style of leadership which has caused unhappiness and demoralization in the institution. This mood has not been helped by what the staff see as the poor and indulgent responses of the UN Headquarters to complaints about Ms. Songwe’s leadership.

The world-wide negative publicity generated by the farce of Mr. Hancock’s appointment has damaged the reputation of the UNECA, a key continental institution. It has also gravely undermined the credibility and standing of Ms. Vera Songwe, the Executive Secretary responsible for the bizarre decision.

The Hancock affair raises important questions about the governance and accountability of the UNECA and its leadership that Africans need to address.

This is an important part of ensuring that we have pan-African institutions that are fit to lead the drive for the realization of an African agenda of socio-economic structural transformation and democratization that advance the aspirations of Africa’s peoples.

SIGNATORIES

1. Abdourahmane Ndiaye, Secrétariat permanent du Rapport Alternatif Sur l’Afrique (RASA)

2. Adebayo. O. Olukoshi, Wits School of Governance, Johannesburg, South Africa.

3. Alice Urusaro Karekezi, Center for Conflict Management (CCM)University of Rwanda (UR)

4. Alice Mogwe, Director, DITSHWANELO – The Botswana Centre for Human Rights, Gaborone, Botswana

5. Alioune Sall, African Futures Institute, Pretoria/Dakar

6. Alvin Mosioma, Executive Director, Tax Justice Network-Africa, Nairobi, Kenya

7. Andrew Karamagi, Human rights Lawyer, Uganda

8. Bench Marks Foundation, Johannesburg, South Africa

9. Brian Tamuka Kagoro, Harare, Zimbabwe

10.Chaacha Mwita – Nairobi, Kenya

11.Chafik Ben Rouine, President of Tunisian Observatory of Economy

12.Charles Abugre, Tamale, Ghana

13.Cheikh Guèye, Geographer, Alternative Report on Africa (AROA/RASA), Dakar, Senegal

14.Cheikh Tidiane Dieye, Director, African Centre for Trade, Integration and development (CACID), Dakar, Senegal

15.Chérif Salif SY, Directeur du Forum du Tiers-monde (FTM), Dakar, Sénégal

16.Chike Jideani, Director, The Ethics and Corporate Compliance Institute of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

17.Claire Mathonsi, Deputy Executive Director,Advocacy Accelerator, Nairobi, Kenya

18.Claude Kabemba, Human rights activist, Johannesburg, South Africa

19.Crystal Simeone, Director, Nawi-Afrifem Macroeconomics Collective, Nairobi, Kenya

20.David van Wyk, Bench Marks Foundation, Johannesburg, South Africa

21.Demba Moussa Dembele, Chair African Association for Research and Cooperation in Support of Endogenous Development (ARCADE), Dakar, Senegal

22.Dieudonne Been Masudi, Ressources Naturelles pour le Département (RND), Kinshasa, D.R. Congo

23.Dzodzi Tsikata, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, Legon Ghana

24.Ebrima Sall, Trust Africa, Dakar, Senegal

25. Élie Kadima, MDR : Mouvement pour les droits de l’homme et la reconciliation, Lumumbashi, D.R. Congo

26.Ernest Mpararo, Secrétaire Exécutif de la Licoco, Kinshasa, D.R. Congo

27.Eunice Musiime – Executive Director, Akina Mama wa Afrika, Kampala, Uganda

28.Firoze Manji, Adjunct Professor, Institute of African Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada.

29.Franck Fwamba, Touche Pas A Mon Cobalt, Kinshasa, D.R. Congo

30.Gladwell Otieno, Executive Director, Africa Centre for Open Governance (AfriCOG), Nairobi, Kenya

31.Godwin Murunga, CODESRIA Dakar, Senegal

32.Hope Chigudu, , HopeAfrica Feminist Consulting Group, Uganda/Zimbabwe

33.Ibrahim Oanda Ogachi, CODESRIA, Dakar, Senegal

34.Idayat Hassan, Centre for Democracy and Development, Abuja, Nigeria

35.Ikal Ang’elei Executive Director , Friends of Lake Turkana, Kenya

36.Isabel Maria Casimiro, Maputo, Mozambique

37.Issa Shivji, Emeritus Professor, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

38.Janah Ncube, Harare, Zimbabwe

39.Jane Nalunga, Executive Director, SEATINI, Kampala, Uganda

40.Jason Braganza, Executive Director, AFRODAD, Harare, Zimbabwe

41.Jibrin Ibrahim, Senior Fellow, Centre for Democracy and Development, Abuja, Nigeria

42.John Githongo – Publisher – The Elephant; Former Permanent Secretary (Governance and Ethics) Office of the President, Nairobi, Kenya

43.Kwasi Adu-Amankwah General Secretary ITUC-Africa, Lomé, Togo

44.Lebohang Pheko, Senior Research Fellow, Trade Collective, Johannesburg

45.Makau Mutua, SUNY Distinguished Professor, Margaret W. Wong Professor, SUNY Buffalo Law School, The State University of New York

46.Michael Uusiku Akuupa, Director, LARRI, Windhoek, Namibia

47.Mike Lameki, Espoir ONG, Kolwezi, D.R. Congo

48.Moses Kambou, Executive Director, ORCADE (Organisation pour le Renforcement des Capacités de Développement), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

49.Mshai Mwangola – The Orature Collective, Nairobi, Kenya

50.Mutuso Dhliwayo, Executive Director, ZELA, Harare, Zimbabwe

51.Nancy Kachingwe, Gender & Public Policy Advisor, Harare, Zimbabwe

52.Ndongo Samba Sylla, Senegalese Economist, Dakar.

53.Okey Onyejekwe, Governance and Development Consultant, Abuja, Nigeria

54.Omano Edigheji, Development Expert, Kaduna, Nigeria

55.Pascal K Kambale, Dakar, Senegal

56.Prisca Mokgadi Gaborone, Botswana

57.Riaz K Tayob of SEATINI (Southern and East African Trade Institute) – South Africa

58.Sarah Mukasa, Kampala, Uganda

59.Shuvai Busuman Nyoni, Executive Director, African Leadership Centre, Nairobi Kenya.

60.Souad Aden Osman, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

61.Sylvia Tamale, School of Law, Makerere University, Kamplala Uganda

62.Tendai Murisa – SIVIO Institute, Harare, Zimbabwe

63.Wanjala Nasong’o, Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee. USA

64.Yao Graham, Coordinator, Third World Network-Africa, Accra, Ghana